Coronaviruses - mouse hepatitis virus and human coronavirus 229E

Thin section and negative contrast electron microscopy of mouse tissue and purified virus.

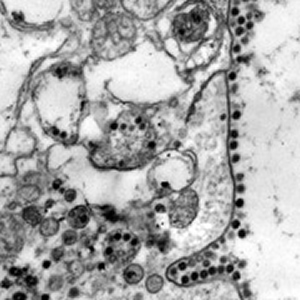

Coronavirus. Mouse hepatitis virus, strain MHV-S/CDC. This virus, formerly called "lethal intestinal virus of infant mice" (LIVIM), is the etiologic agent of a lethal enteritis, the most important disease of infant laboratory mice [see Hierholzer JC, Broderson JR, Murphy FA. New strain of mouse hepatitis virus as the cause of lethal enteritis in infant mice. Infect Immun. 1979 May;24(2):508-22.]. This is an ultra -- thin section of the small intestine of an infant mouse at two days post-infection when the mouse was moribund. Virions have accumulated upon the plasma membrane of this intestinal epithelial cell as a result of transport from sites of virion production in the endoplasmic reticulum and exocytosis via membrane fusion -- the virions then stick to the outer surface of the cell. Magnification approximately x40,000.

Micrograph from F. A. Murphy, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas.

Download TIF

Coronavirus. Top, human coronavirus 229E; bottom, mouse hepatitis virus, strain MHV-S/CDC. Negative contrast electron microscopy. Classical negative contrast images of coronaviruses are really not the way they look when in their native state. The peplomers (spikes) fall off so easily that most images seen in atlases and textbooks are really partly "bald." Native virions are actually so heavily covered with peoplmers that virions might not be recognized if only the classical images are in mind. Here, the top micrograph represents the classical image and the bottom micrograph the way coronaviruses look in their native state. Magnification approximately x60,000.

Coronavirus. Top, human coronavirus 229E; bottom, mouse hepatitis virus, strain MHV-S/CDC. Negative contrast electron microscopy. Classical negative contrast images of coronaviruses are really not the way they look when in their native state. The peplomers (spikes) fall off so easily that most images seen in atlases and textbooks are really partly "bald." Native virions are actually so heavily covered with peoplmers that virions might not be recognized if only the classical images are in mind. Here, the top micrograph represents the classical image and the bottom micrograph the way coronaviruses look in their native state. Magnification approximately x60,000.

Micrograph from F. A. Murphy, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas.

Download TIF

Human coronavirus 229E. The same image as above, but colorized. Negative contrast electron microscopy. Classical negative contrast images of coronaviruses are really not the way they look when in their native state. The peplomers (spikes) fall off so easily that most images seen in atlases and textbooks are really partly "bald," as are these. Native virions are actually so heavily covered with peoplmers that virions might not be recognized if only the classical images are in mind. Magnification approximately x60,000.

Human coronavirus 229E. The same image as above, but colorized. Negative contrast electron microscopy. Classical negative contrast images of coronaviruses are really not the way they look when in their native state. The peplomers (spikes) fall off so easily that most images seen in atlases and textbooks are really partly "bald," as are these. Native virions are actually so heavily covered with peoplmers that virions might not be recognized if only the classical images are in mind. Magnification approximately x60,000.

Micrograph from F. A. Murphy, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas.

Download TIF