Dr. Jim Zhang (Photo Credit: Duke Global Health Institute)

Dr. Jim Zhang began his career studying the adverse health effects of air pollution in the 1990s, which formed the foundation of his PhD dissertation at Rutgers University. His work naturally led him to take an interest in global health, and he subsequently developed many international connections – particularly in his home country of China. He describes traditionally working with clinicians (often pulmonologists) in studying how pollutants affect the lungs, cardiovascular, and reproductive health and how this burden can be reduced.

His partnership with Dr. Gray was a more recent development, beginning in 2013 while they were both faculty members at Duke. Dr. Gray had had a fruitful relationship with the Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences (MNUMS) for many years and, in the interest of exploring two of Mongolia’s most troublesome public health concerns, collaborated with Dr. Zhang. These two public health concerns include unclean air and respiratory infections. The aforementioned NIH funding is thus directed at several longitudinal studies in Ulaanbaatar, where participants and their homes have been recruited for data collection.

“My Impression is that [study] participants are friendly and supportive; we have reached the target number of recruitments without issue,” Dr. Zhang shares. Some 200 households have been recruited to date. He visited several of these homes himself last summer and helped measure pollutant levels. Participants are also offering repeated collections of biologic samples (such as blood for immune measures), respiratory function data, and clinical assessments examining for viral illness. “The challenge so far has been data analysis by colleagues at the Medical University,” which includes trainees pursuing Masters degrees, “and then, deciding how to write up findings, given English is not their native language.”

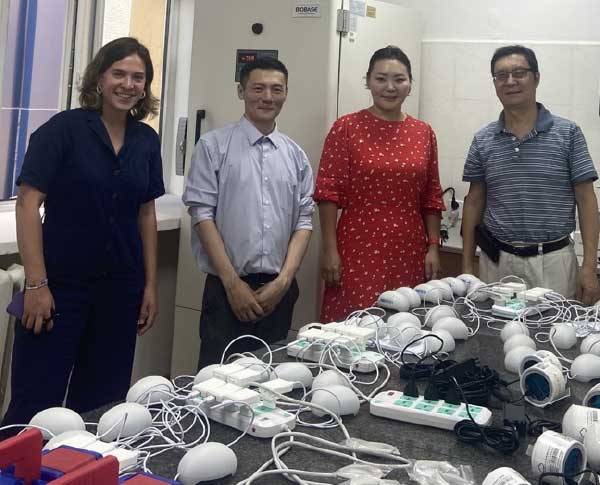

Research collaborators looks over a table with field equipment used to measure air pollution while meeting in June of 2023 at Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences [left to right: Lauren Pox (Duke University), Jargalsaikhan Galsuren, PhD (MNUMS), Professor Dambadarjaa Davaalkham (MNUMS), Professor Jim Zhang (Duke)]. (Photo Credit: Dr. Gregory Gray)

Dr. Zhang is encouraged about the future of their studies. Air pollution in Mongolia is well-documented in the literature, fueled by long, cold winters that necessitate space heaters run predominantly on coal. Even in modern homes with central heating, boilers are still powered by coal, likewise contributing to combustions that produce smog and exacerbate susceptibility to respiratory disease. Many Mongolian homes use coal-heating stoves to prepare food as well. The geography of Ulaanbaatar provides another challenge, as the city is located in a valley; the result is a dangerous nexus of a cold climate, a storm of pollutants, and the coalescence of these pollutants over the valley. “Ulaanbaatar suffers one of the highest respiratory infection rates in the world,” shares Zhang.

Eventually, Drs. Zhang and Gray and their Mongolian and US colleagues (led by Dr. Robert Tigue from Duke University and Dr. Davaalkham from the MNUMS) plan to conduct cell culture studies. Analysis of data being collected now will hopefully divulge how pollutants affect the immune response and the cell types involved – the hypothesis in question being that pollutant exposure impairs the human defense in regard to viral infections.

When asked about future direction beyond this research, Dr. Zhang hopes that the study results can be used to support government policies. “The [Mongolian] Government realizes the problem. [They] already have an incentive program to use processed coal over unprocessed coal.” Based on other studies, Dr. Zhang is not sure that these incentives will bring enough reduction in pollutants to make detectable changes in health outcomes. Yet by bolstering the current body of knowledge with their findings, he hopes to aid the government in developing strategies to further lower pollutant levels, cultivate interest in improving health results, and provide a framework to the rest of the world for how pollution exacerbates vulnerability to viral respiratory illness.

View of Ulaanbaatar’s mountain view impeded by smog (Photo Credit: catalystplanet.com)