With suicide being the third leading cause of maternal mortality in the U.S., nurses at UTMB Health are on a mission to end the stigma surrounding maternal mental health.

Championing the cause is Souby George, a nurse clinician V with the Mother Baby Unit in John Sealy Hospital in Galveston.

George has two goals for her work in this area.

- She aims to spread information about perinatal or postpartum mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs), which can present as depression, anxiety or psychosis during pregnancy for up to a year after childbirth.

he wants women to know that PMADs can happen to anyone, and they should be comfortable coming forward if they or a loved one is struggling.

“Since I’m a front-line nurse, I want my patients to go home with a feeling that they have the support and resources if they want them,” George said. “I want them to feel like they were heard.”

Supporting George in this effort is her colleague and mentor, Dr. Vanessa Abacan, clinical nurse specialist with the Women’s Infants and Children’s Department in John Sealy Hospital.

To show their patients and the communities they serve that even those who work in the health care field experience these conditions, George, Abacan and four of their colleagues have come forward to share their own personal PMAD battles.

While their specific scenarios vary, each participant shared a desire to be open and vulnerable so other moms can feel less alone on this journey.

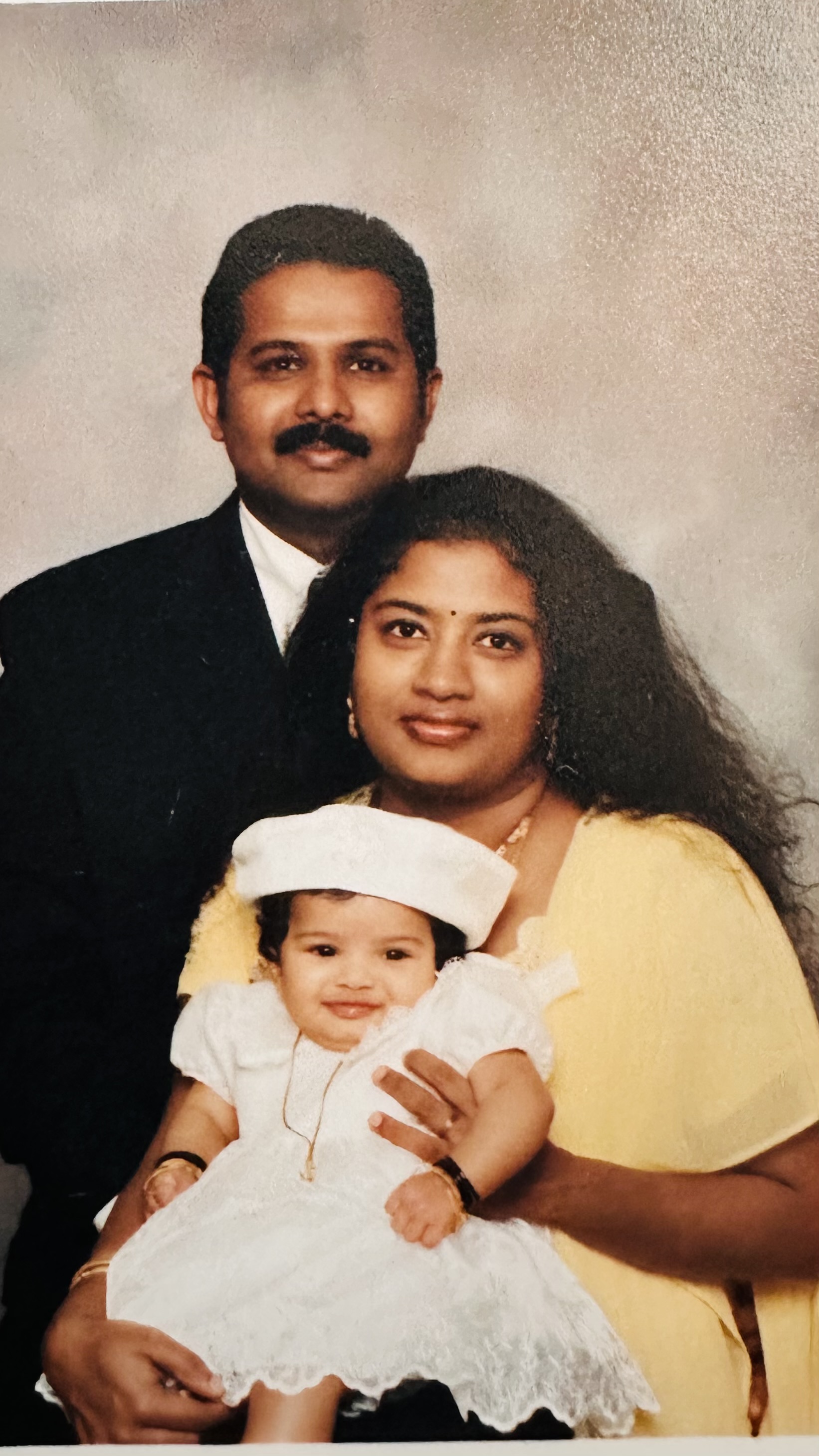

Souby George, mom of 2, nurse clinician V with the Mother Baby Unit in John Sealy Hospital in Galveston

A mother for 20 years, Souby George recounted the early days of motherhood with her first-born, her daughter, like they were yesterday.

George’s experience: “I lived in the future and missed a lot of stuff happening right then and there,” she said, reflecting on the early days with her first-born child.

Previously diagnosed with stage four endometriosis, George wasn’t sure she would ever be a mother, so her daughter was a miracle baby. But the excitement and joy from that miracle quickly turned to confusion and worry after her daughter was born.

“For me personally, I was never depressed; instead mine presented as anxiety,” George said, reflecting on her postpartum feelings. “I was anxious about everything and constantly worried something was going to happen to me and I wouldn’t be alive to tell my daughter all she needed to know and people wouldn’t know how to care for her.”

A new mom in her late 20s, George’s feelings were compounded by the fact that her mother was unable to be with her as she had planned.

“Her visa wasn’t approved to travel into the U.S., so I felt alone, even with my husband here,” she said. “It was all such a blur with my daughter. But with my son, I felt so supported. It was so different, and I think a big part of that is because my parents were there.”

As the memories came back to her, she used words like “helpless” and “hopeless” to describe herself after her daughter’s birth.

“I went through [PMAD] without knowing what it was,” she said. “I was very confused and because of my life experiences, I went back to school to study PsyD and also earned my Perinatal Mental Health certification These decisions allowed me to better understand both myself and others.”

What resources helped? George didn’t use any resources, as she was unaware of what was available to her. When she tried to seek help, going to the emergency room around six months postpartum for what she thought was a panic attack, the clinicians dismissed it as a hypertensive crisis, since she was previously diagnosed with hypertension. They never screened her or asked if she recently had a baby. She’s hoping this work will make it easier for others to get the help they need when they need it without feeling overwhelmed

Advice for other moms: “I want them to know that they're not alone. One in five have some kind of perinatal mood disorder. That means it’s very common and they need to start talking about it and identifying the people who are going to be there for you without judging.”

Parting thought: “If we don’t take care of our mothers and their mental health, we’re not just doing a disservice to them but also to the next generation. We want mothers to be mentally present with their babies. PMADs compromise parenting which reinforces the underlying mental health condition and adversely affects the child’s physical and emotional development.

Dr. Vanessa Abacan, mom of 1, clinical nurse specialist with the Women’s Infants and Children’s Department in John Sealy Hospital

Dr. Vanessa Abacan’s journey as a mom began almost three years ago when her daughter was born.

Abacan’s experience: Abacan’s mom was a postpartum nurse and a board-certified lactation consultant; she passed in 2018, before Abacan was married or pregnant.

“Going through this milestone without her was triggering for me. I didn’t have issues with bonding; mine was more so anxiety,” she said.

As the days passed during Abacan’s postpartum journey, she realized in addition to the anxiety, she was feeling a bit depressed, too, but it only fully came to light after her OBGYN stepped in.

“It took a lot for me to admit that I was depressed,” she said, mentioning how even though she dismissed her feelings as “just how it was supposed to be” her doctor prodded her during a screening during one of the postpartum follow-up visits. “When I got to the question, ‘Are you crying every day?’ and I said yes, my doctor immediately intervened.”

After that telling visit, Abacan was prescribed medication to help with her symptoms. She’s still taking medication today, although the dosage has been tapered down, and she wants people to know there’s absolutely nothing wrong with needing a prescription to help with this condition. It’s no different than taking medication for any other ailment.

What resources helped? Medication and primary care provider appointments and check-ins.

Advice for other moms: “It’s important for women to know it’s OK to not be OK – if you are having trouble sleeping, or feel constantly , irritable, or anxious, be cognizant of that and know it’s not a bad thing to speak up.. We have to normalize mental health. It's a matter of listening to yourself, listening toyour feelings, to your body, to your mind. You are not alone and there are resources available to help you.”

Parting thought: “You need to listen to the people around you and not be scared to ask for help. It can affect anyone, and it is okay. I know as moms we put the pressure on ourselves to be strong all the time, but you need as much care after birth as your baby does.”

Laurie Chabouni, mom of 2, assistant nurse manager with Pediatric Med Surg, John Sealy Hospital

For Laurie Chabouni, PMAD symptoms were something she never experienced until her second, most recent pregnancy.

Chabouni’s experience: “I was just a little moody before he was born, but really after my youngest son’s birth it became extreme,” Chabouni said. “I had a lot of mood swings, there was lots of crying like on a daily basis and exhaustion, just pure exhaustion. I was very irritable and was experiencing lots of fear and anxiety.”

Chabouni, who in addition to her almost 2-year-old also has a 20-year-old son, tried to find logical ways to explain why she was feeling that way.

“I tried to attribute all of these feelings to my age, my job, you know just different things to almost normalize it,” she said. “But I knew deep down that I was not feeling the way I should feel.”

Ready to take charge of her situation, Chabouni made an appointment with her primary care provider approximately six months postpartum.

During that visit, Chabouni screened positive for postpartum depression.

“At that point, my doctor wanted to start me on medication,” she said, noting that she personally was not ready to start taking anything for her symptoms just yet.

“Around the nine-month mark, I realized I might need some help, so I finally agreed to try the prescription, and it helped,” she said. “I probably needed it a lot sooner, honestly.”

What resources helped? “Medication really did help me a lot. It made a big difference in the way I felt, my crying episodes were fewer and I felt a sense of peace that I had not felt in a while. ”

Advice for other moms: “Use your support person. Open up to them. Talk to them and then take the help. When people offer help, take it!”

Parting thought: “One thing that I started doing that kind of helped me understand how I was feeling was taking notes. Journaling is not possible for me when I've got a very active baby, but taking notes like on my phone of the way I'm feeling in certain moments ... it helped me put it in perspective. Like OK, I do need to go talk to someone about this. So just as those feelings are coming up, we try to discount them and say. ‘Oh, you know things are gonna get better tomorrow when I've had a little bit more sleep.’

But taking notes shows how it can compound, and it gives you something to talk to the doctor about and show them.”

Asheia Randolph, mom of 2, lactation consultant with the Angleton Danbury Campus labor and delivery, recovery and postpartum team

When Randolph became a mom for the first time, she was alone, in the military, in a foreign country.

Randolph’s experience: “I was very void of emotions,” Randolph said, describing her situation after having her first child. “I was focused on the baby, but I did not develop a loving connection. It’s almost like she was a pet, just another responsibility.”

Randolph went on to describe that she thought everything she was experiencing was normal.

“I thought this is what it is like after having the baby,” she said. “I made sure I checked off all the boxes, but I was not developing a relationship.”

Being alone in another country, she said, it was hard for her to notice or identify an issue at all.

It wasn’t until around nine months postpartum when a provider at Randolph’s work started noticing things weren’t quite right with the new mom. The provider asked Randolph a number of questions, closing with, ‘Do you feel like you love your baby?’

Randolph answered bluntly with her first instinct.

“At first I felt very shameful after she asked me the question,” she said. “I answered, and that’s when I started to think, ‘Woah, something must be wrong with me.’”

Thankfully for Randolph and her baby, she was able to start therapy just a week after that exchange with her colleague.

“I went to see the therapist at least once a week for about four months,” she said. “It was just talk therapy, teaching meditation and just really talking through the emotions and where they may have stemmed from. I did exercises to work on just connecting.”

While Randolph may have felt void of emotions during the early months of her postpartum journey, she did manage to exclusively breastfeed her daughter throughout her first year of life. She even used her lunch breaks to breastfeed her daughter during the day at daycare.

In fact, Randolph credits the breastfeeding with keeping her daughter safe.

There was one particular night when the baby’s cries woke up Randolph.

“I don’t know what happened, but I woke up and she was crying, and I put her in a car seat, turned the closet light on and set her in the closet and went back to bed,” she said. “Not 10 minutes later I jumped out of bed, as I was physically in pain needing to release some milk. I believe that could have been a horrific night, but breastfeeding saved us.”

Randolph feels the passion for what she does now as a lactation consultant stems directly from her personal experience with breastfeeding.

What resources helped? “Talk therapy in person and over the phone. Lots of meditation and reflecting and journaling.”

Advice for other moms: “Always follow your good instinct and cling to your resources that are near you, whether that be family, friends, medical resources. Never be afraid to say, “This is happening, and I don't know why but I need help.” Don't sit in silence. Speak confidently to someone about how you're feeling, no matter what it is.”

Parting thought: “It was important for me to share my story because so many women go through so many different emotions, and we don't share it because of the shame or the embarrassment or just feeling like we're not adequate because we feel this way. I want to help end that stigma and hesitation.”

Jacqueline “Jackie” Meyer, mom of 2, nursing program manager, with the Nursing Program Development team in Rebecca Sealy

It was more than a decade ago that Jacqueline Meyer experienced some pretty significant feelings while postpartum with her oldest daughter.

Meyer’s experience: “I clearly met the criteria for being diagnosable and probably could have benefited from some sort of intervention, but I just blew it off because I didn’t know any better,” she said. “I think I knew based on the fact that I was a nurse, but I refused to accept the fear and the fact that something was wrong.”

Her oldest, who was a preemie, was born with a heart condition, only adding to the stress Meyer was feeling.

When reflecting on that time of her life, Meyer is positive it wasn’t psychosis she was feeling, but she was definitely depressed.

“It was more this feeling of, ‘Why can’t I fix this baby?’ mixed with anger that I couldn’t control, and it could have hurt her,” she said.

She recounts a specific night where she felt she afraid she would hurt her then newborn.

“I was immature, I didn’t have a supportive partner and, in that moment, I remember I was like, ‘I’m just going to drop this kid,’” she said.

She also mentioned feeling depressed and anxious around all the uncertainty her new life posed with a baby who was sick, in the NICU and on medication.

“I remember just trying to figure out the whys,” she said “Why does she have heart problems? Why is she in the NICU? Why does she need this medicine? Why do we have to put her through all of these tests? The list just went on.”

As she continues to unpack the feelings of those early months and years of motherhood, Meyer lands on a big thought she had.

“I didn’t think I could be good enough as a mom or a nurse,” she said. “Looking back, in retrospect, that was a hot mess. The whole postpartum period. Thankfully, nothing bad happened, but it could have.”

Meyer said she didn’t begin to feel a sense of calm and reassurance in her abilities as a nurse and mom until her first born was roughly a year old.

“I was like, OK, we maybe did it,” she said. “She survived even though I was mediocre.”

What resources helped? “While they weren’t available to help me, I think filling out surveys and screenings as they’re available to you. It’s the best first step to give your colleagues and providers the right numbers to get you access to other resources you may need.”

Advice for other moms: “Complete the questionnaires correctly and honestly so they can screen you, diagnose you and get you the help you need.”

Parting thought: “We need to continue to be proactive and share the stories of moms in the trenches and the paths they took to get help if they needed it.”

Haley Castillo, mom of 1, nurse clinician IV with the Angleton Danbury Campus Labor and Delivery, recovery and postpartum team

Haley Castillo’s life as a mother began with a trip to the hospital that left her stranded nearly an hour away from home during Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

Castillo’s experience: Admitted to a hospital near her home in Brazoria County for an infected C-section incision, Castillo had to be transferred to the Woodlands area to ensure continuity of care during the storm. Thankfully, her baby and mom were able to be with her, but the rest of her family including her father, sister and husband were all still miles of flooded streets away.

Once the water subsided and she was able to go home, she hoped to settle into a routine with her new little family; however, that’s not at all what happened.

“I was probably four or five weeks postpartum, and I remember crying all day for absolutely no reason,” she said, noting that she was rather tearful from day one of her postpartum journey. “At this point, it was so normal for [my mom and husband] to find me crying this way.”

Desperate for help, Castillo called her OB and informed her team of what was going on.

“I said, ‘Hey, I’m not OK,’” she said. “I’m very depressed and have a lot of anxiety.”

Rather than support, though, Castillo was met with a lack of answers and directions to call someone in psychiatry because they couldn’t help her there.

The less than helpful response left Castillo feeling lost and discouraged.

“I just hung up and didn’t reach back out for help until my son was 18 months old,” she said.

During that gap waiting for help, Castillo felt myriad emotions and considered a number of scenarios, including what it would look like if she left her family, or even worse, what it would be like if she took her own life.

“I had a bag packed and I kept it in my closet,” she said, convinced her son would be better off without her.

Thinking back, she realizes she was never screened for any kind of anxiety or depression at any stage during her pregnancy or postpartum journey.

“I was not screened at the hospital or during my postpartum check or even when I called to reach out for help,” she said.

Eventually through working with her insurance, and at the urging of her mother, Castillo found a counselor and saw her for a few months. Her primary care provider also was able to get her started on some medication.

Now almost seven years later, Castillo mentions that the pain from that experience is a big reason she hasn’t gone on to have more children.

“I knew that I could not physically, or mentally, have another baby because I just didn't know if I would make it through,” she said.

What resources helped? Medication and therapy.

Advice for other moms: “Have an accountability partner. It could be a spouse, a parent, a sibling, a friend, just someone to help keep you honest with yourself and the situation.”

Parting thought: “I wanted to share my story so that we can hold ourselves accountable to make sure that what happened in my scenario doesn't happen to anybody else. We may not be able to prevent perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, but what we can prevent is someone not getting the help that they need.